BLOG POST BY PTAC MEMBER REBECCA GIBBONEY Elena Aguilar states in her book Onward that it takes about “10,000 hours of deliberate practice to become a master at something as complex as teaching” (p. 239). And yet, here we are, teaching through a pandemic--a pandemic that has turned our Picasso masterpiece into a blank canvas. Fall of 2019, I would not say my canvas was a masterpiece, but it was a work in progress. However, as I sit here almost a year since we were isolated by the pandemic, I stare at a blank screen--a blank canvas, not exactly sure how to write my thoughts on paper, not exactly sure how to reach you. Like many of you, I have so many questions. Yet, my questions target a different audience --YOU! As a former teacher turned professional development provider, I have so many questions. Some have answers. Some seem impossible. Some still have me holding onto hope. How can I create professional learning opportunities that do not feel like one more thing for educators? How do I help educators believe they are enough? How can I… My incomplete masterpiece in the past could not possibly be the exact same work of art in the future. I had to let go. I had to find a way, one brushstroke at a time. A yellow streak, understanding new learning management systems. An orange streak, turning professional development opportunities into professional learning opportunities (yes, there is a difference) through gamification. Blue streak here, there. Green streak. Asynchronous. Hybrid. Synchronous. Remote. Slowly but surely, my blank canvas is getting some color. Each of us has a blank canvas. All we need to do is pick up a new brush. Perhaps, try a whole new paint. We all need to paint through our unknowns and sometimes beyond the lines, new perspectives; because with each stroke, we will create our own kind of masterpiece. The ultimate question is, what kind of masterpiece will you paint? Aguilar, E. (2018). Onward: Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

0 Comments

BLOG POST BY PTAC MEMBER JAKE MILLER The year “1920 was an auspicious year for a young person to enter the world as an American citizen.” Journalist Tom Brokaw used these words to introduce us to “The Greatest Generation,” those Americans born between 1901-1927. In his epic book of the same title, he shares how they grew up watching the world become more authoritarian abroad, eventually leading to the outbreak of The Great War (now World War I). The war was followed by the 1918 Influenza pandemic (also known as the Spanish Flu), where 50 million people died across the globe (including 675,000 Americans) -- more than double (and quintuple) the number of war deaths. Once the virus was under control, there was a decade of a new normal and explosive growth until the stock and job markets collapsed, thus beginning the long, painful journey of The Great Depression. There this generation remained stymied for another decade until war broke out. When their country called them to service, whether it was fighting on front lines or stepping up personal sacrifice and increased production at home, this generation quite possibly saved the world. What if the group of students before us, in 2021, is the next Greatest Generation? The historical outline above hardly is a recipe for replication, but there are more than enough rhymes to allow us to consider it. To start, 2020 is an equally auspicious year for a young person to enter the world as an American citizen. As a social studies teacher, former staff member at the Pennsylvania State Capitol, candidate for office, organizer for Pennsylvania State Education Association, and promoter of youth voices in government, I’ve said this more about politics and government in the last calendar year than ever: “Well, I never saw that happen before.” GOVERNMENT Whether it’s the Black Lives Matter or Q-Anon, “Stop the Steal” or a second Presidential Impeachment, or any other events that have tested the elasticity our democratic-republic like a trampoline, students are becoming Constitutional scholars if only because the events of the world have made it a priority to understanding - and fixing - them. Additionally, while adults like to debate and surmise the difficulty of making sacrifices of wearing a mask to get this pandemic under control, this generation expresses the resilience needed to outlast and outmaneuver a pestilence. While others gawk at the slow crawl of immunization rollout - especially here in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania - children don’t even have a vaccine trial to look forward to. And yet they continue on. K-12 STUDENTS Graduating seniors enter quite an uncertain world already. However, 2020-21 has proven to be the most auspicious; that’s led to necessity being the mother of invention and brother of intention. Schools and their teachers - whether at the college level, community college, certification programs, or high school - have had to pivot more than those on the ice of a Flyers-Pens’ game. And, though far from perfect, teachers have mostly met the students where they are. To say high school students and teachers are struggling to perfectly meet one another’s needs is an understatement. But what if the important lesson students taught us isn’t perfection - or isn’t in a textbook? What if it was the auspices of tenaciousness? At the middle school level, where I teach, coming of age with all the hormones and anxiety of the age is already quite a task. Even the most confident and successful adult can recollect some dour feelings of pubescence. While students have stumbled and failed more than ever, what if the lesson these kids teach us is resilience -- and personal ownership of their learning? Less than 20% of schools are back to full-time instruction, and that impact has been hardest on elementary students, where attention spans are low and even lower behind a screen. Ask any parent of a Kindergartener, and you’ll know exactly what I mean -- or of any third-grade teacher who needs to see another kid bring another pet to the screen. And while pundits (wrongly) mention how schools are “closed” (they’re not) and how 2020-21 will be “a lost year,” I have a bigger question: What if this the year that redefines the American future, and these kids lead us there? COMPARISONS WITH THE GREATEST GENERATION I’m sure the adults who were raising the Greatest Generation had more than their fair share of doubts about the kids before them. The decrease in life expectancy was unparalleled. The number of America’s sons and daughters lost to war and then disease was comparable to the suffering in the Civil War. Jim Crow was at a crescendo, and anti-black racism led to an egregious amount of mistreatment and even lynching. The difficulty in determining who or what was “an American” extended to other groups, as Irish and Indigenous found difficulty. A decade of growth in the Roaring 20s was a dream that would pop and crush this generation just as much. But when the time came to show their resilience, they heeded the call and met the challenges as best they could. My hope is that this group sitting in our classrooms seats, the Zoomers, will be our next Greatest Generation. A CALL TO ACTION But our hope is not enough. The time for action to bridge these gaps is now. The way to make sure that this generation of students before us is the Greatest Generation and not the Grounded one. That’s why the Pennsylvania Teachers Advisory Committee has stepped up to share:

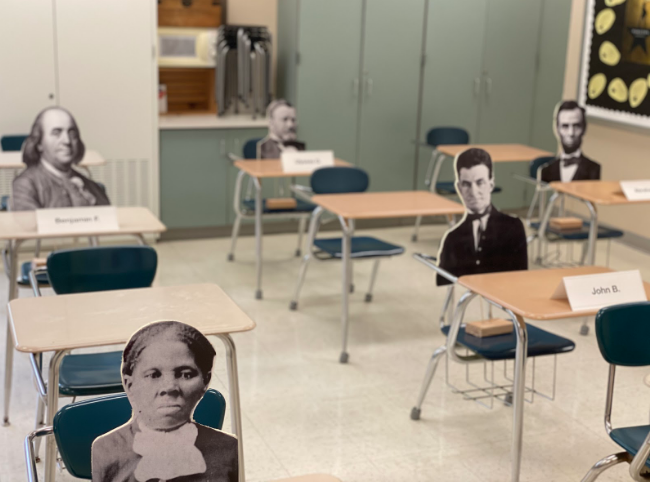

Which brings us back around to 2020, our most auspicious year for a young person to enter the world as an American citizen. In this year, it is the teachers who will bridge that gap and give students every chance to transform into the Greatest Generation. Maybe it will be the year this generation proves themselves beyond our every doubt. When we work so they may rise, we’ll once again say, in the most positive proclamation, “Well I never saw that happen before.” BLOG POST BY PTAC MEMBER BJ ENZWEILER I write this blog post on Jan 7, 2021, a day after the protest, insurrection, sedition, attempted coup, or whatever you want to call it. Like many Americans, I was appalled by what I was seeing at our national capitol building. In a desperate attempt to understand, I flipped through different news sources on an almost minute-by-minute basis. Three screens, my phone, and my two computer monitors all showed news sources until I couldn’t take it anymore; sulking, I crossed the street to Rite Aid to buy a whole box of Tastykake Chocolate Bells. I needed to consume sugar to try and sweeten an incredibly bitter day. Now, a day later - with more hours of news and chocolate bells devoured - I’ve given myself some time to reflect on what has happened and what it means for me as an educator. This is an educators’ blog after all. I want to understand the cause of what happened on January 6th in Washington DC. The first assumption my brain jumps to is that we need more critical thinking in this country. This idea has been tossed around so much that it has almost become axiomatic. But, I must pause and think about my own experience and what I know of the teachers I have met. All of the teachers I have known in my decade of experience have tried to push for critical thinking in their classrooms through their own disciplines. We have used projects, Socratic seminars, and debates to push our students to see the world more broadly. We all know about the necessity for critical thinking in all classrooms, and we have known this for decades. To say that the current and former students of the United States schools have not had critical thinking training is reductionist. We should not discount the efforts of our fellow teachers across the nation. Many of us have pushed our students to take different perspectives and know that our students are thinking critically. There are definitely other root causes of the events of January 6th. I think one of the more important causes is tribalism. This is blind loyalty people are expressing to demographics, religion, and political affiliation. With the rise of the internet, social media, and more politically focused news sources, we are able to choose our social groups and information. As such, political discourse has more easily turned into echo chambers that inflame the rages of sedition. Tribalism comes from a deep human desire for belonging. We must remember that we humans are still animals; we are social creatures with a basic need for connection. The tribalism of the 2010s and on comes from the community building that humans will always do. Tribalism appeals to our base nature and can circumvent our critical thinking when we are angry, hurt, and vulnerable. So what do educators need to do? When people feel underappreciated and unheard, rabid tribalism can emerge. Therefore, we should recognize our human need for connection and listen to all of our students’ pain and perspectives. We need to continue to teach perspective-taking and critical thinking, but something else must be present too: compassion. Always recognize the humanity and pain behind the rage. In our classrooms, we should not ignore whatever crazy news is going to happen in 2021. Instead, we must talk about it with our students. No, we don’t all teach current events, but showing our humanity is a slow but positive step towards anti-tribalism. With all of the directives and paperwork, this can seem like another thing that has to be added on to the workload. Compassion is not more work; instead, it is a methodology. We should inject empathy into all interactions we have with our students. Let’s not allow anybody to feel so sidelined that they turn to rabid echo chambers online or elsewhere. We should hear our student’s views to make our classrooms safe and stable spaces. Let’s be available, and let’s be kind. And, maybe have a few more emergency Tastykakes stashed away somewhere. BLOG POST BY PTAC MEMBER, ALICE FLAREND, PH.D. Students usually see teachers as having finished school and, therefore, finished learning. However, the need and the drive to learn new things are integral parts of being an educator, both as an inherent trait and as a result of external forces. I earned a PhD a few years back, and that process threw me back into a nascent learner mode. I had to learn not only a new language (e.g. epistemology, cognitive versus sociocultural constructivism), but I also developed a new social science way of viewing the world. This brought into sharper focus how I push my students to explain all the motions in the visible world with a few principles and with unfamiliar use of the familiar words, such as force (comes from the interaction of objects), acceleration (not just speeding up), and energy (specifically defined). I was once again riding the roller coaster of learning: the frustrations of not understanding, the doubts of whether I could understand, and the elation when I finally could understand. I was in the same emotionally charged position in which I placed my students and was reminded just how difficult learning is. My learning journey improved my teaching by pushing me to build stronger relationships with my students to help them manage the emotional swings and to build stronger ties between my curriculum and their prior knowledge to help them navigate to deeper understandings. All of my students come with different prior knowledge, experiences and understandings. As a teacher, I need to learn these particulars about my students and then help them fill in the gaps and further their individual knowledge. This means taking the time to listen to the voices of my students as they tell me about themselves, their ideas and their questions. It also means the classroom activities will look different for different students. Fast forward to teaching in times of COVID. With little warning, my fellow educators and I were thrown into the uncomfortable world of being learners of technology with a deadline and with hundreds of students, parents and community members counting on us. I need to help my students learn during these stressful times but without the means to look over a shoulder at the student device, or more importantly, without being able to look them in the eye. My students are willing to simply click, secure in their cavalier view of technology that nothing cannot be undone. I, as an adult, am less adventurous, having unwittingly transferred funds between accounts with one of those simple clicks. My mistakes as a teacher are visible to and affect the lives of my students and their families. Posting wrong Docs, giving assignments on sites that cannot be accessed on certain devices, missing student responses that need an answer can all contribute to losses of learning and faith in schooling. I felt and still feel awash in a dazzling forest of technology without much of a map. I am one of the lucky ones because my science and engineering background means that at least I have a foundation of programming and electronics which fills out a bit of the map. I understand that computers only know the syntax of the commands given not what we intend to do. This does not, however, mean that I know why sometimes my text comes out backwards on EdPuzzle questions or that I am able to predict how a Doc will look on an iPad versus a Chromebook versus my laptop. One of the only good things to emerge is that once again I am in touch with the world of the learner, hopefully, pushing me to be a better teacher. BLOG POST BY 2020-2021 PA TEACHER OF THE YEAR AND PTAC MEMBER JOE WELCH Each May, my middle school holds an awards ceremony for our 8th grade students. We celebrate their accomplishments, highlight their kindness and contributions, and hear from administrators, teachers, and students. At the end of it, we roll the annual reflection video with Jason Mraz’s “Have it All,” amongst others, serenading us in the background. And, even though I may have seen the video cut dozens of times before airing live, I always get that lump in my throat. Lyrics like “Here’s to the lives that you’re gonna change” or “May the best of your todays be the worst of your tomorrows” ring true. But, really, it’s the line “I want you to have it all” that captures the sentiment I - and so many other teachers - have for students as they begin the next chapter of their story. We want them to all to have the access, the opportunity, the support, the confidence, the resilience, the inspiration, and the character to experience all that life has to offer them. But right now, they can’t. As full disclosure, I opened the school year teaching in a semi-hybrid format, then virtual, then live hybrid, and then back to virtual. The yo-yo that is the 2020-2021 school year has put students in a position where they just cannot, as Mraz writes, have it all. They should have the experiences and opportunities that others before them have had in year’s past. Teachers want them to have that - and more. But, we, as local communities throughout Pennsylvania, need to be better at adhering to health officials’ recommendations and guidance so that our students can get back to having it all. It is beyond time to acknowledge that. Are teachers and students coming together to do amazing activities to foster learning? Absolutely, we are. And, we’re doing a great job in the situation that we have had dropped in our lap[tops]. Trust me, teachers across the state [and nation] are doing their best to innovate and inspire. After four months of collaborating, training, planning, and adapting, educators have, once again, shown their resolve and are proving that their dedication to students will not waver but grow stronger, especially in the face of adversity. I have had the opportunity to experience this first hand. As the year opened, a small, but diverse group of educators from different schools and communities throughout Western Pennsylvania collaborated with their local PBS Affiliate, WQED, to produce high-quality lesson content to serve students throughout the entire viewing area of the network. This collaboration led to recording over-the-air lessons and units, producing engaging activities that can be implemented with or without technology resources [which leads to a greater conversation about educational equity]. Colleagues and I have worked to broadcast live lessons from historic sites around Pittsburgh as well as day trips to Fayette County and Washington, D.C. Teachers are willing to literally go the extra mile for students. Again, we want our students to have it all, to best experience it all, and to know throughout it all that they are our priority. I am also proud to be part of a group of teachers that filled their hybrid classrooms with historical figure cut-outs, social justice leaders, entrepreneurial role models, and local heroes to fill the physical voids students may feel in their classrooms when desks were left vacated due to social distancing and hybrid models. This is all part of what it means to do what is needed to connect with our students, and teachers are rising to the occasion and then some. We all want students back in school, experiencing everything, with everyone, as soon as it is safely possible to do so. Students have been working under difficult circumstances as well. Some are trying to attend class while caring for siblings, some have family members who are sick, and some students are victims of a lack of equitable technology resources. We have seen some of the best that our students have to offer over the last four months, and, on the flip side, a spotlight also now shines on the need for equitable reforms now and in the future. Students’ resiliency, their perspectives, their positive attitudes as changes are thrust upon them, certainly are helpful fuel to press forward. However, the fatigue of students and teachers is setting in. The sustainability of this marathon that is 2020 is in question.

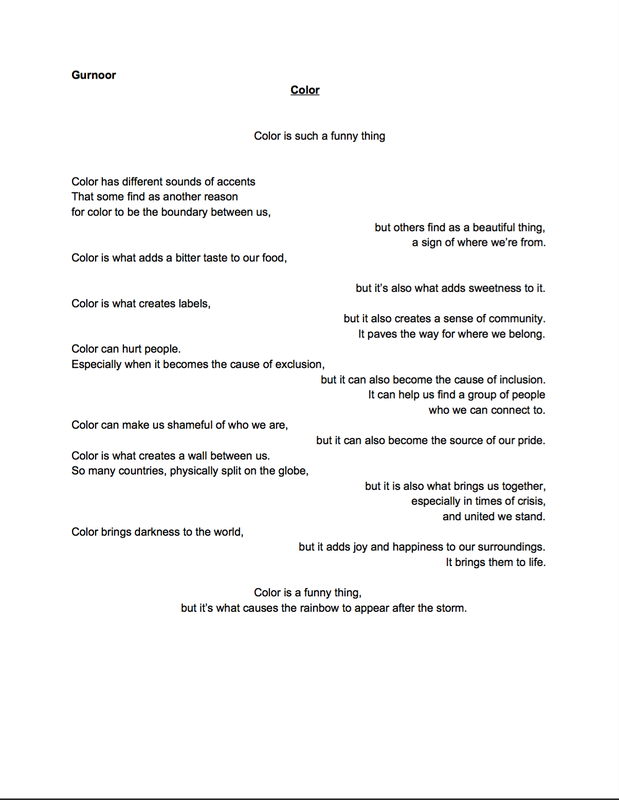

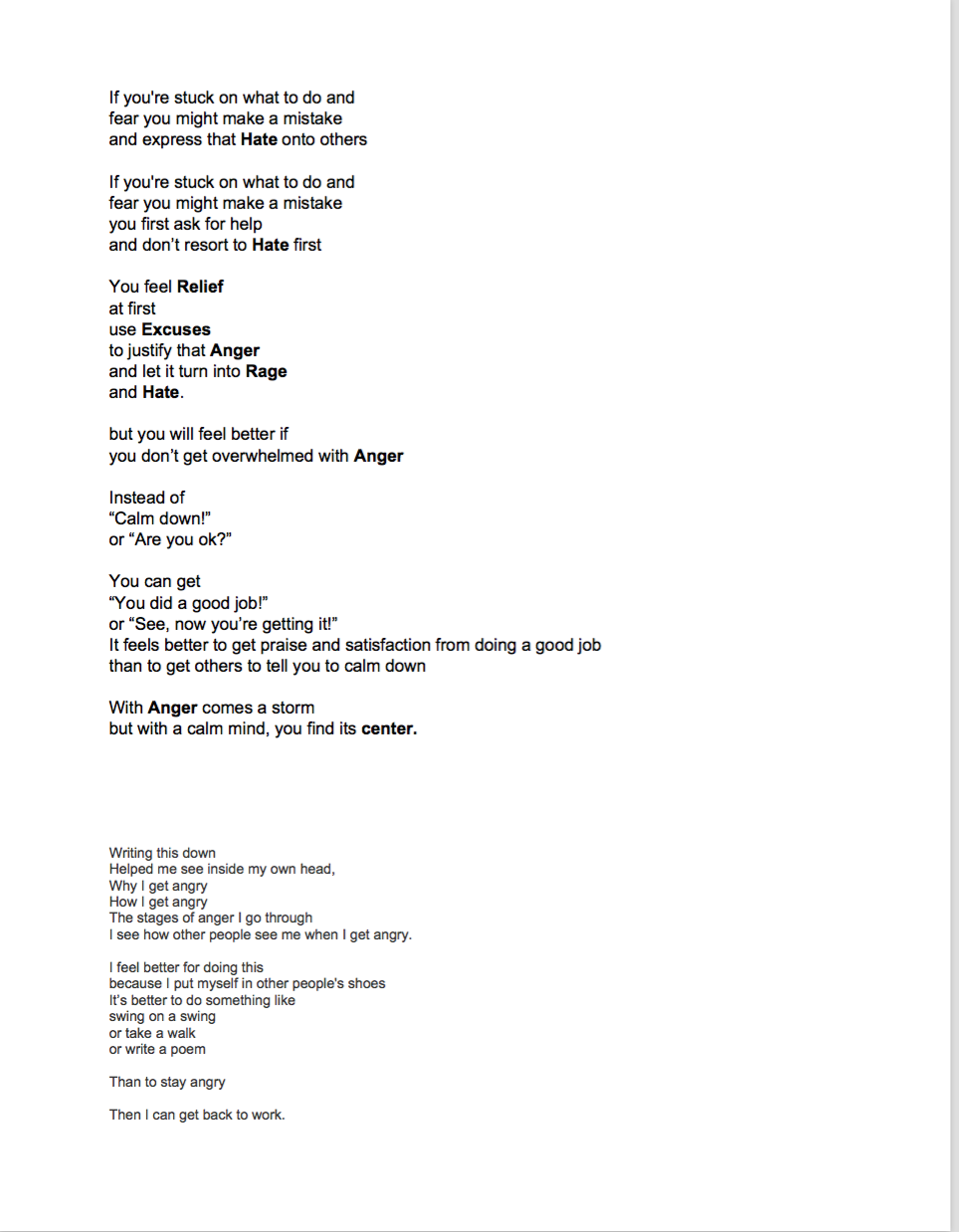

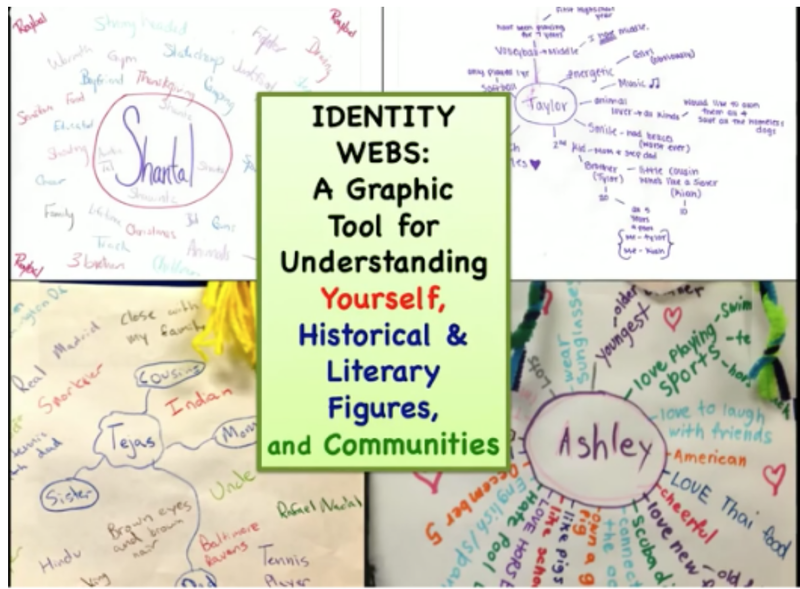

I’ve been putting off writing this for weeks. I wanted to make sure to have a positive spin on what I wanted to write. A feel good story, if you will, about what I had mentioned above. About how it is all working out for everyone, with a clear narrative that teachers are working harder than ever [and we are], and are sacrificing and risking more than ever [and we are], and will continue to be able to sustain it. But, that is just more of the toxic positivity that is detrimental to moving forward. In stressing about this recently, a colleague I consider to be a mentor shared, “Joe, some situations just aren’t all positive.” So, let’s have the conversation. Unfortunately, despite all of the innovating, all of the collaborating, all of the inspiration that teachers, students, and communities are making happen in our schools, schools are slowly being forced to close physical spaces yet again. As scientists and doctors have predicted, not following safety recommendations has led to a rise in community spread. I, like hundreds of thousands of teachers across Pennsylvania, want students back in school. I do my part to make sure that this happens, like hundreds of thousands of Pennsylvania teachers. And, like hundreds of thousands of teachers across Pennsylvania, I am willing to make personal sacrifices and make the decisions in my own life, in and out of school, to put us in a better position to be able to do this safely. Making these choices so that a kindergartner has a better chance of in-person reading instruction? A no brainer. A middle school student has a better chance to participate in their first musical? Sign me up. A high school senior can hug their friends at graduation? Who wouldn’t pick that? These are personal decisions that keep me and my family safe and keep others safe. These are decisions that teachers and so many others across the Commonwealth are wisely making. But they are also the decisions that are necessary if we want to return to normalcy as we await the cavalry in the form of mass vaccinations. But, until that point of widespread distribution, we need your help now more than ever to make this a realistic possibility. I want the students to have it all. I want to sit in a full auditorium in May surrounded by students and have that annual lump in my throat. Put simply, I want students to be in school. Please, help us make this happen. BLOG POST BY PTAC MEMBER SUSAN MATTHIAS After taking part in a workshop, “Developing a Growth Mindset in the Middle School Math Classroom,” I began to understand that it is the classroom culture that could positively impact the manner in which students approach their work. Although this workshop focused on math instruction, the concept of developing growth mindset in students can be applied to any content area on all levels. If you have ever heard statements such as “I have never been good in math”; “I will never be able to write an essay”; “This science experiment is too difficult”; “This math problem has too many steps”, you are most likely working with students that operate using a fixed mindset. These students see their personal qualities as fixed traits that cannot be changed. Students with fixed mindsets do not recognize the connection between effort and success. With a fixed mindset, they believe that skill and intelligence are qualities you are born with and cannot be improved upon. A growth mindset classroom culture can teach students that they are in control of their learning. Once students begin to understand, and most importantly, believe they are in control, an empowering mindset begins to creep in. My classroom culture begins with me. After I adjusted the manner in which I responded to students,I began to see change. My responses to students began to communicate my confidence in them as the learner. In the past, when students came to me with questions and problems, I would be tempted to jump in and fix it for them. I stopped doing much of the work for them. What I realized is that learning stops when I respond in that way. I began to change how I responded. I began to ask more questions such as “Tell me what you do know about this problem,” or “Tell me how you got to this point.” The questions I began to ask and the discussions that ensued began to empower the students. I heard students say, “I got this!” or “I will work on that.” Yes, a growth mindset is all about empowerment. Students need to understand that learning takes work and effort, and often, does not come easily. When students begin to experience success after doing their work, they begin to feel empowered. In a growth mindset classroom, students understand that a response such as “I don’t know” is not accepted. When students are not sure of how to respond, they learn and practice other responses such as “Can I phone a friend?”; “Can you come back to me?”, “I need a few minutes to think about that.” If teachers refuse to accept “I don’t know”, they promote a classroom culture where learning can happen, even if that learning does not appear to happen immediately. It takes time and patience to develop a classroom culture that promotes a growth mindset. Educating students about the difference between a fixed mindset and the benefits of growth mindset opens doors they once thought were closed. It takes a strong teacher commitment to develop a growth mindset classroom. Discussions and responses to students must encourage students to do the work. At first, students may push back, as it will feel uncomfortable to them, however, if done consistently and with compassion, the culture will change. Although results will not be immediate, when promoting a growth mindset culture, I assure you that they will begin to try harder and reach deeper. They begin to be more accountable for their work and become more independent. Students will then be in charge of their learning! Blog Post by PTAC Vice-President, Mike Soskil Today I embark on my twenty-third school year journey. Each one has been exciting, difficult, rewarding, and unique. As I look forward to this school year, I can’t help but reflect on the incredible challenges I faced during my first year teaching. There were times it felt like I didn’t have a clue what I was doing and others when I didn’t think I’d make it. When I look back, though, I realize that it was the greatest year of professional growth of my career. Most importantly, despite all of the difficulties, I know I made a positive impact on my students that year. Three days before the 1997-98 school year began, and less than 24 hours after arriving in the Sonoran Desert after a cross-country drive, I met the Program Director of the Mesa, Arizona school in which I had landed my first teaching position. She welcomed me. She laughed at me because I was wearing khakis, long sleeves, and a tie on a 115 degree day (I was trying to look professional and make a good impression). She showed me my classroom. Then, she handed me three photocopied teachers manuals: an old math book, a phonics book, and a spelling primer with a copyright date of 1898 (really). These were to be my only curriculum or teaching guidance for that entire school year. I was terrified. But at the same time, I was so excited that I couldn’t sleep. Finally, after all of my university courses, my student teaching, and my dreams of making a positive impact on the world through teaching, I was going to get the opportunity. I made a lot of mistakes that year. Sometimes I wish I could go back in time and talk some sense into the relatively clueless first-year teacher version of myself. I learned a lot, though. And, with each mistake, each new experience, each new challenge, each colleague that I connected with out of necessity, I grew as a professional and a person. In a strange way, I was blessed at the time with the humility that comes from knowing I was clueless. As a first year teacher, I didn’t expect to have it all figured out. I did my best, all the while knowing that my best was going to continue to get better. I’ve come to understand that the incredible challenges that I faced that first year were the groundwork for the innovation and experimentation that has allowed me to be successful in my career. If I could figure out a way to find resources and to teach with almost no guidance or mentorship provided by my school, I could figure out a way to teach anything to anyone. Now, like many of you, I’m right back here at the beginning. As I begin this year, I’m once again clueless. I’ve never taught concurrently - online and in-person at the same time. I’ve never had to worry about the physical, mental, and emotional health of my students, my colleagues, or my family in the ways that will be necessary this year. It’s harder because I know now - much better than I did back then - what effective teaching looks like. So, I’m giving myself permission to make mistakes, learn, and grow this year. I’m not going to be as effective at first - because none of us are. Our students’ needs are different, our challenges are different, and our restraints are different. But, with each new challenge comes and opportunity to grow, and an opportunity to model for our children how to learn from mistakes. I’m giving myself permission to focus on the social-emotional health of my students more this year, and to be at peace with the fact that it might mean there is less time for academic content. After all, all of us have been impacted by this pandemic, and we can’t Bloom unless we Maslow first. I’m giving myself permission to innovate and experiment, because the only way to the other side of this pandemic is through it. And, for those of you who need someone else to tell you, I’m giving you permission to make mistakes, to focus on your students’ holistic needs, and to innovate as well. This school year will be different than any other you’ve ever experienced. As teachers, we tend to be perfectionists, believing that our value is measured by our ability to teach the curriculum. When we have quiet moments of reflection, however, we all know that our value as educators is much more closely tied to our ability to connect with our students and help them see their value. As the inevitable uncertainty unfolds this year, carve time and space for you to remember, honor, and focus on that. Surround yourself with other educators (virtually if needed) who inspire you and help you do that. You aren’t alone. PTAC’s network of outstanding, inspiring teachers will be working with you to ensure narratives from our classrooms are informing the decisions in Pennsylvania that impact our students. Experience tells me that they will also be coming together to help each other, me, and you build networks of support and collaboration. The challenges may be new, but the solution in education remains the same. Relationships will get us through this school year. With colleagues, and with the students that we love. Teachers have a capacity to empathize and show compassion on a level found in few other professions. It’s never been more important for our students or our fellow educators. If we get those relationships right, at the end of this year you and I will look back at all of the struggles and know that we had a positive impact on our students. Decades from now, our current students will be asked by their grandchildren, “What was it like to live through the Pandemic of 2020-2021?” My hope, for my students and for yours, is that they begin telling that story by saying, “There was this incredible teacher…” Fox Chapel Area High School Music Department students welcome faculty, staff and administration back to a new year!BY PTAC MEMBER COLLEEN EPLER-RUTHS, Ph.D Inspired by a conversation during a recent meeting, I set out to find out what my students felt about their new experience in online learning with me and overall. In some ways, I was driven by my fear of the future. What if we are online next fall? Would students flock to a virtual school? Is there a place for a brick and mortar teacher in this COVID world? Can I craft working relationships with a new set of students in a digital environment? For context, my school district is considered rural but we do have one town and one very small city included in our population. We have 48% free/reduced lunches and about 10% minority (mostly Hispanic and/or Black). We are one of the districts in the state where a portion of our population has no internet access due to either poverty or location (rural without internet providers). For that reason, our spring semester was considered “enrichment.” We held online classes and office hours, provided online work (or packets), and provided graded feedback. However, the students were not held responsible or accountable for the assignments. Second, I teach computer science and physics, so I was already using technology in my classroom. My students were used to using Google Classroom, Documents, and Sheets. I felt my students would easily make the transition to online learning. My anonymous 16-question survey was split into three parts - questions about them, questions about my online classroom, and questions about school overall. I had a mixture of scaled questions and open-ended questions. First I asked what they valued in education. Then I asked questions about their engagement with my classroom and what I did that was good and where I needed to improve. Finally, I asked them what they miss about brick and mortar school, and what they liked and didn’t like with online school. My final question was “any other thoughts?” I was humbled by their perspectives and thoughtful considerations. While some of the feedback was something I could correct right away (“get a better camera, I had a hard time seeing in class” and “slow down”), some of the feedback spoke to my heart and what I am beginning to understand about the student COVID experience. So today, I am going to focus on what my students valued, what they need and what they miss and don’t miss about the brick and mortar school. The first set of questions were designed to help my students first focus on the learning context and their educational values. My first question was “What do you value in education?” 67% of my students suggested that gaining knowledge and skills was valuable to them. “I do not want to take a class just to pass and advance to the next level. Instead, I want to understand and grasp the topic at hand. By understanding what I have learned, I can take this knowledge and become a successful adult. “ 22% of my students valued the teachers: “Learning challenging material, but with the help of my teachers.” “A teacher who is always ready to help and makes themselves available. I also get a lot more out of in person teaching, but I understand that it isn’t an option right now. “ The rest of the students valued having fun, learning for the real world, and for humanity. “I value anything that benefits the welfare of humanity. Mainly, I value education that makes me better than I was the day before, not only intellectually but makes me a better human. “ The students’ answers about educational values generally made me feel that our students are engaged in learning and do care about how we teach. My second question was “I wish my teachers knew…” I normally ask this same question as a test question during the first semester in the fall. I am often blown away by the variety of personal information and insights students will reveal. I was just as impressed by the candid responses and different perspectives I got in my online class survey. Three general themes ran through the survey answers: 1) students struggle with a lack of motivation, 2) online learning can be hard, time consuming and not as good as being in person, and 3) being stuck at home is taxing on mental health. Students gave genuine answers. “I wish my teachers knew that we as students do not understand the topic as well as the teacher does. Students do not like the feeling of being downgraded because "the topic is easy" or barely teaching us because the teacher thinks we understand.” “I wish my teachers knew how much pressure I put on myself and how grateful I am to them for being patient and kind.” “I am infinitely gracious to those whom teach with respect, and whom understand they are still very similar to me, as I am human and so are they. “ “While I try to do most of my work for most of my classes, if I did absolutely everything for all 7 of my classes and went to every Google meet, I wouldn't have time to do anything else.” “How my motivation to learn has been diminished more and more since being stuck at home. I try to stay busy, and for the most part I do stay pretty active, but I do have some days (or weeks) where I can’t bring myself to do much at all. “ Reading candid thoughts from my students helps me to tailor my classroom to their needs and be more reflective on my goals for them. I started to include information on my classroom announcements about social emotional learning, reaching out to guidance if they find themselves overwhelmed, and getting outside to hike and enjoy the outdoors. I also encourage them to contact me directly through email or office hours. Finally, I made sure I talked with each student as they came into the digital classroom to see how they were and how they were doing with physics content. At the end of the survey I asked my students “what do you miss about coming to the brick and mortar high school?” There were no surprises in that many students reported missing friends, teachers and interactions with people (47%). Interesting enough, students also missed motivation and the routine (23%) and hands-on learning (17%). “ I miss seeing my friends and teachers. I also miss being in the classroom because I feel like I learn much better that way.” This is good news for those of us concerned with brick and mortar schools going the way of horse and buggies. Interactions with people, routines, and hands-on learning are our strongholds in physical schools. Only a small percentage (12%) suggested that they didn’t miss much. “I do not believe I would have grown as much as I have if I had continued going to brick and mortar school. Education is so much more than a grade.” Next, in comparison, I asked the students “What do you like about online learning?” The most common answers were the ability to set their own learning pace (24%) and have a flexible time schedule (24%) and sleeping in (12%). “You can do it in the comfort of your own home and at any time you want.” But a significant group of students (18%) said they like nothing about online learning. Only 6% of the students liked learning without receiving grades. Overall, I am not surprised by these results. Online learning does offer flexibility and freedom. But, I was surprised more students didn’t suggest lack of grades being a good thing. As an educator, I have always dreamed about a world where grades didn’t matter, but the reality is that our society values putting a number to effort. Is there a place for curiosity and learning for the joy of learning in the high school? My last question was “What do you not like about online learning?”, Students had a wide variety of dislikes about online learning too. Many of the complaints had to do with the lack of schedule or accountability. “The lack of real schedule, to me it didn’t feel like a school day, just a day where I did some extra work.” “I don't like that work isn't mandatory, that we don't get grades. Even if I do all of the work, I feel like I'll be behind next year because of how long it has been since I've had an honest test, or actual grades.” Other students felt overwhelmed, unorganized, and unable to communicate: “Sometimes hard to keep on track with work” “It's harder for me because I like to be able to physically write things down on paper, and I would like to be able to ask questions in person because I feel like I get more out of it that way.” Overall, online learning is just not the same as in person. Students didn’t like staring at the computer all day, not being pushed, feeling unproductive and were concerned about falling grades. “I believe that myself and others have lost motivation ...Online learning is not the same as physical, real life learning.” Many of these complaints about online learning are going to be hard to overcome. But we must put thought into these shortcomings if we have to continue with virtual school into the fall. As educators, we have to help our students build a consistent schedule, get organized and become self-motivated so we all can find success in this new digital world into which we have been thrust. At the end of the survey I asked my students if they had other thoughts. I was encouraged by the general positivity of my students and their resilience. “I enjoyed your class while it lasted” “I think online learning has potential, but I'm still not ready to go all in.” “Thank you for doing all you could to make this year better through all the horrible events that have occurred.” “I am very happy with your transition to online learning. Even with this big change I am still able to learn and hear your silly jokes during the meets. Thank you for truly caring about my education along with other students, it really shows.” And understood their sense of loss: “I'm going to miss my high school, believe it or not, and all the teachers that believed in me when I couldn't believe in myself. I originally thought that when I would leave high school, I'd coming running out cheering and happy to get away from it, but now I'd give my left leg to attend one more in-person class, to bump into someone in the hall, to hear other kids laughing, to see my teachers in person, to have my ears attacked by the sounds of slamming lockers and the loud, boisterous teachers in the school, and to say goodbye to the lunch ladies in the cafeteria.” *Sniff* So what have I learned from my survey? First, I found that my students really do care about education, learning and working with their teachers. I also now know that they carry a great load - school, work, family and activities - and the COVID lock down has made motivation and mental health even more of a challenge. I also believe that there is still a future for a brick and mortar school where we can help students one-on-one, give them a routine and time to interact and learn with other people. But, we also must learn to embrace this digital world and think outside the brick-and-mortar box. Online learning does have many benefits including pace and freedom to follow your curiosity and passion. While my survey will not help me predict the future for the next school year, I know the future will be in good hands with the students who have learned to thrive in our new normal. BLOG POST BY 2014 PA TEACHER OF THE YEAR FINALIST AND PTAC MEMBER TRACEY FRITCH AND Julie MIKOLAJEWSKI In her 2018 New York Times bestselling book, So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo states,“You have to get over the fear of facing the worst in yourself. You should instead fear unexamined racism. Fear the thought that, right now, you could be contributing to the oppression of others and you don’t know it. But do not fear those who bring that oppression to light. Do not fear the opportunity to do better.” So You Want to Talk About Race grew from Oluo’s experiences in attempting to personally unpack and explain challenging issues related to race and racism, then realizing she had a knack for helping people figure out how to engage in conversations about race, with the hope of making progress and creating change. Now, more than ever, in spite of the challenges inherent in facing and discussing important social issues, including the challenges encountered during conversations about race, public school teachers must cultivate culturally responsive teaching in their classrooms. They must strive to model the process of creating connections with others, especially those who are different from themselves, all the while working to participate in and foster authentic classroom conversations about social issues, thus encouraging and teaching students to do the same. This past June, the Pennsylvania Teachers Advisory Committee (PTAC) issued its “Recommendations for the 2020-2021 School Year.” Inside the first recommendation on student well-being was this statement: “We recommend every school district embrace culturally responsive teaching and learning. This should incorporate history inclusive of marginalized perspectives and literature that represents and celebrates diverse cultures and individuals.” Though many people, including many well-meaning educators, avoid what they perceive to be challenging conversations about race or other social issues for many reasons, including fears of making mistakes or being perceived negatively, it has become increasingly clear that, for many, the choice to avoid these conversations is a privilege. Given recent world events, this is a privilege onto which we can no longer afford to hold. As Maya Angelou famously stated, “When you know better, you do better.” Each day, our students look to us for guidance and leadership regarding both their academic and their social-emotional learning; as we foster culturally responsive classrooms, we provide safe spaces in which a diverse range of individuals feel included, supported, and able to thrive. Identity Work In order to be culturally responsive and to fully prepare our students for the mutli-dimensional world in which they live, teachers must choose to address recent events of racism, discrimination and bias in the news, as well as acknowledge that events like these are not new occurrences. Students are keenly aware of the current socio-political climate and are looking to the adults in their lives to offer guidance in both processing it and in discussing it openly and respectfully with others. Taking time to foster conversations about identity, diversity, and character development are not only best practices in literacy learning, but these conversations also foster classroom community development and prepare students to be educated and engaged citizens in a democratic society - hopefully a society that is inclusive and promotes understanding of equity and the strength of diversity. This diversity includes diversity of race, ability, gender preferences, and sexual orientation, among others. At a middle school in a Philadelphia suburb, Tracey begins each year with her students by asking them to create “identity webs,” a ritual learned from the professional book Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry, by Smokey Daniels and Sara Ahmed. Students spend time, in class and at home, examining, listing, and discussing the various aspects of their “identities.” This list includes, but is not limited to, student reflections upon age, grade, gender, hobbies, passions, culture/ethnicity, languages spoken, favorite foods, personality traits, and family composition. Students share whatever information feels comfortable as they use the webs to introduce themselves to classmates, and learn about the ways they are both similar to and different from others, as they build classroom communities. Similarly so, Julie begins the year with students creating identity portraits that depict both visible and invisible aspects of her students’ identities. This activity was borrowed from Gary Gray Jr., an educator in Singapore. Initially, these conversations about personal identities can be tentative and even awkward, but they gradually evolve, with encouragement and guidance, into frank, empathic conversations, and set the tone of these classrooms as - this is a place where we respectfully discuss important matters, even when it sometimes feels initially uncomfortable to do so. Inevitably, discussions about students’ personal identities lead to literary discussions of the identities of the characters in the novels they read, and the ways those identities shape the characters’ perspectives and choices. Later, as these middle schoolers compose poetry, they often choose to reflect upon various aspects of their identities from a social justice standpoint; they consider the way their identities shape their lives, impact their choices, and guide the ways in which they hope they can impact the world. As well, when students create characters for their fiction stories, they first envision the characters’ identities, and the way those identities will shape their characters’ responses to, and solutions for, the conflicts in the stories. What begins as highly personal work leads to cultural awareness, authentic opportunities for personal growth and self-expression, as well as participation in respectful discourse about identity and social issues. Diversifying Classroom Libraries & Fostering Diversity in Student Independent Reading Alongside the crucial nature of open, respectful classroom conversation, students also need to be offered authentic ways to explore a wide variety of cultures and perspectives, including ones not directly represented in a classroom community. Though students of color currently comprise more than 50% of U.S. public school students (Public School Review, October 2019), according to the School Library Journal (in 2018) only around 23% of children’s books published had a main character that was a child of color. This startling disparity underscores not only the need for culturally relevant pedagogy, but also a need for increased diversity in the composition of classroom and school libraries. In 1990, Rudine Sims Bishop coined the now-famous metaphors of books serving as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. In a video interview published by Reading Rockets in 2015, when asked why children and schools needed diverse books, Bishop answered: "We need diverse books because we need books in which children can find themselves, see reflections of themselves… children need to see themselves reflected. But books can also be windows. And so you can look through and see other worlds and see how they match up or don’t match up to your own. But the sliding glass door allows you to enter that world as well. And so that’s the reason that the diversity needs to go both ways. It's not just children who have been underrepresented and marginalized who need these books. It’s also the children who always find their mirrors in the books and, therefore, get an exaggerated sense of their own self-worth and a false sense of what the world is like, because it's becoming more and more colorful and diverse as time goes on." As we live through these times of dramatic social change, it is imperative that teachers and schools provide students with texts that incorporate the full complexity and variety of human beings who exist in the world - and include protagonists that represent the full diversity of the human experience. The idea that books can, and should, be windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors for students is not a new one, but, now more than ever, this concept needs to move to the forefront in order for educators to ensure that not only are the students seeing themselves in the books that they read, but that students are also grappling with the complex nature of human identity, particularly related to individuals who have different lived experiences from their own. By cultivating the practice of reading texts that offer opportunities for students to perceive others in the world more authentically, students gain empathy, cultural competence, and can then more adeptly engage in the work of equity, empathy, and anti-racism. Diversifying classroom and school libraries is an ideal first step for educators seeking to develop cultural competence in their students. At times, as teachers begin to think about taking on challenging conversations, many wonder if certain topics are “too much.” While it is, of course, essential to consider developmental appropriateness of texts for various ages, most children and young adults have natural curiosity and deep empathy for others’ lives, and are eager to learn about and discuss others’ experiences. Newbery Medal winner and past National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature Jacqueline Woodson is often asked about the ways in which she takes on what some might consider challenging topics in her books. To answer, she notes that her work as an author, particularly one for tweens and teens, has taught her that children are acutely aware of issues in the world and that they truly want the important stories of their and others’ struggles to be seen, heard, and understood. In addition to the way that reading books about diverse characters promotes empathy and understanding, these books also provide natural and authentic ways to open necessary discussions. In an author appearance in fall 2018, Woodson noted, “There is so much history in this country around the way people were and continue to be mistreated - and the challenge is, always - how do I tell this story in a way that’s not didactic? How do I tell this story in a way that’s respectful and loving? And how do I tell this story in a way where I can show the hope in it? And that’s always timely, that need for hope in a narrative.” Reading and discussing well-written, engaging children’s books affords teachers a natural and authentic opportunity to talk with kids about race, bias, and discrimination of all kinds, as these topics arise. Because of the presence of a beloved character and engaging narrative, the conversations are not, as Woodson says, “didactic,” but instead, thoughtful, thought-provoking and empathic. If a teacher or school librarian is at the beginning of this journey in diversifying a library, they should begin with what they have, inventorying their libraries to look at the types of books which are (and are not) there. Educators should first eliminate outdated books with stereotypes, identify the themes and identity groups that are somewhat lacking or not present, and then begin to purchase well-written titles based on recommendations from others further along in the journey; following thought leaders in the field on social media is an excellent way to find new favorite authors. Students and families often enjoy helping with this work, noticing trends in a library and making suggestions for improvement. Thrift stores, online yard sales, and library sales are excellent, inexpensive resources in quickly adding numbers of books, as are used booksellers such as Better World Books, which donates a part of its profits to causes that bring books to people in need. Donors Choose and First Book are also helpful in raising funds for building libraries. Scholastic book orders and book fairs yield “points” with which teachers may purchase books. When asked, friends and family members who have finished with books in their homes will often happily donate them to a school. In addition, in many districts, some curriculum funding in schools can be successfully redirected toward adding authentic literature choices, and away from more traditional textbook/workbook options, often for far less money and with the result of far greater student engagement. For more information on diversifying classroom and school libraries, including choosing diverse authors for addition to (particularly middle school) libraries, click here. Please feel free to share in the comments if you want to suggest someone we’ve missed! Once the new books begin to arrive, it is important to get them into students’ hands. Simple routines that create a “buzz” around particular novels or authors often have immediate and significant impact - teachers and students can create “book buzzes” (or author buzzes), in which they describe aloud or in writing what aspects of particular books/authors they enjoyed, and to whom they might recommend them. This also works by placing books on a white board ledge with a quick note jotted above it. Typically an early-in-the-year routine, Book Tasting (like wine tasting) allows students to quickly peruse and “sample” a teacher’s library, noting titles of interest and discussing them with others. These routines result in what is known as “blessing” of those books and authors - and circulation of them increases dramatically. In these times of social distancing and virtual learning, these procedures would likely need to be adapted, but can still take place. It is important to include both widely-relatable books about everyday experiences such as friendship that happen to feature a diverse variety of characters, as well as to include books focused on “social issues” related to those characters - lest we give students the impression that children of color, children with disabilities, and/or children with differences in gender identity or sexual orientation (or other ways of being diverse) only have lives fraught with upheaval related to those identities. Over time, we need to find ways to continually track the balance of texts in libraries - many students enjoy sorting and categorizing books and helping with this work (though perhaps this will be a more appropriate activity once our current pandemic ends); it can also be helpful to use the free web tool, Booksource Classroom Organizer, which, once set up, will not only perform library audits to check for diversity, but also offers a free online platform with which to manage no-contact book checkout. Delving into Deeper, More Courageous Conversations After the initial “buzz” over these books and authors is created, teachers can begin to delve into the deeper conversations naturally inspired by the literature and identity work. While facilitating these conversations can be a complex task requiring effort and care, it remains an extremely important one. Despite the fear, discomfort, or reservations that teachers may have, we are long past the time in which it is appropriate for these conversations to be avoided; thankfully, there are many excellent resources to support us in doing so. Teaching Tolerance offers a guide titled Let’s Talk (2019) that can be an excellent springboard for teachers just starting out. Two other helpful resources in framing and structuring this discourse come from the work of Glenn Singleton (Courageous Conversations About Race) and Diane Goodman. Among other ideas, Singleton’s “four agreements” help to foster spaces that eventually allow for deep dialogue about race, racism, ethnicity and privilege. Participants are encouraged to “stay engaged, experience discomfort, speak your truth, [and] expect and accept non-closure” (70). On her website, Diane Goodman offers resources on building cultural competence for promoting equity and inclusion, and also shares sentence frames for crafting responses to the microaggressions and bias which will arise up in fledgling, honest conversations about culture and race. Unavoidably, conflict, discomfort, and non-closure will occur in these conversations, however, teachers must encourage children to continue to engage in the conversations, despite these difficulties. Singleton reminds his readers that ‘mistakes” and misconceptions will happen, but by staying engaged, students’ communities can become places of healing and change. In his best-selling 2019 book, How to Be An Antiracist, Ibram Kendi advises his readers to eliminate the term “racist” as a slur or pejorative about a particular person. Instead, he asks us to use the word descriptively, as “the only way to undo racism is to consistently identify and describe it” (9). Once we can observe, describe, and discuss racist actions, thoughts, statements, systems or policies (or classist, sexist, ableist, or homophobic ones), we can then begin to go about the work of unpacking and dismantling them. Both authors of this blog post, though they teach in different school environments, one large urban and one suburban, utilize reading and writing workshops as their adopted literacy curricula. This allows us a fair amount of curricular freedom in adding diverse texts to the curriculum and encouraging our students’ independent reading of a wide variety of diverse texts. However, even teachers whose curriculum is more scripted or laid out on their behalf usually still have some agency in choosing short mentor texts for demonstrating teaching points, in choosing more diverse whole-class texts for longer-term study, and/or in encouraging and guiding students’ independent reading lives. The more that, through diverse texts, students are exposed to a greater variety of lived experiences and challenges, the more they encounter identities different from their own, the easier it will be to broaden horizons in a way that fosters greater cultural competence, and, hopefully, eventually, inspire positive actions for creating a fairer world for all. Moving Forward Recently, Newbery author and current National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Jason Reynolds was featured as a guest on the “On Being” podcast with Krista Tippett. A Newbery winner, and passionately devoted to children’s well-being, Reynolds has most recently published what he calls the YA “remix” of Ibram Kendi’s powerful and ambitious historical text, Stamped from the Beginning. During the podcast, Reynolds noted that creating “fortitude in the minds and bodies and spirits of young people” is his calling. The topic of Reynolds and Tippet’s podcast conversation was “Fortifying Imagination.” He says this about culturally relevant pedagogy and talking with students about antiracism: "They know. And so, if they know and we’re not helping them process, now it’s become more dangerous than you’ve ever imagined. So, we have an opportunity to lean into the discomfort of having to talk to kids about this, in order for them to find language around it... But how does one keep an imagination fresh in a world that works double-time to suck it away?... I think that the answer is, one must live a curious life. One must have stacks and stacks and stacks of books on the inside of their bodies. And those books don’t have to be the things that you’ve read—that’s good, too, but those books could be the conversations that you’ve had with your friends that are unlike the conversations you were having last week. It could be about this time, taking the long way home and seeing what’s around you that you’ve never seen… What if you were to explore the places around you? What if you were to speak to your neighbor and to figure out how to strike a conversation with a person you’ve never met? What if you were to try to walk into a situation, free of preconceived notions, just once? Once a day, just walk in and say, I don’t know what’s gonna happen, and let’s see. Let me give that person the benefit of the doubt, to be a human… There’s no finish line...It’s a muscle that has to be developed...antiracism is simply the muscle that says that humans are human. That’s it. It’s the one that says, I love you, because you are you. Period. That’s all." This beautiful conversation was reminiscent of the way that Woodson, in her bookstore appearance, acknowledged the need for “hope in a narrative,” and of the way Oluo asks us not to “fear the opportunity to do better.” In these turbulent times, educators would do well to begin the process of cultivating culturally responsive teaching in their classrooms through literature - leading to conversations that are both authentic and sometimes uncomfortable - but the sort of productive discomfort that leads to growth and systemic change. Our children are watching us - and waiting for us to provide guidance - they need to hear our (and each others’) voices as we do the hard work of guiding them toward the hope in our nation’s narrative. Not surprisingly, the best way for educators to find “hope in the narrative” is when we see the way that culturally responsive instruction inspires students to consider and share their own identities in the work they create - both in writing and in classroom projects and conversations. Two talented and introspective seventh graders, Gurnoor, a young woman of color, and Justin, a young man working to learn to manage his anger more effectively, wrote the following poems after studying mentor poems and poets in a middle school writing workshop, while learning virtually in the spring of 2020. Sources Cited

Daniels, Harvey “Smokey,” and Sara K. Ahmed. Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry. Heinemann, 2014 Goodman, Diane. www.dianegoodman.com. “Responding to Microaggressions and Bias.” https://dianegoodman.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Responding-to-Microaggressions-and-Bias-Goodman.pdf Goodman, Diane J. www.dianegoodman.com. “Cultural Competence for Equity and Inclusion: A Framework for Individual and Organizational Change.” 20 April 2020. https://www.wpcjournal.com/article/view/20246 [Summary at: https://dianegoodman.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CulturalCompetenceforEquityandInclusionDianeGoodman.pdf] Institute for Educational Leadership. “Courageous Conversations About Race Protocol Overview.” https://iel.org/sites/default/files/G10-courageous-conversation-protocol-overview.pdf Kendi, Ibram. How to Be an Antiracist. One World, an imprint of Random House, 2019. Oluo, Ijeoma. So You Want to Talk About Race. Seal Press: 2018 Public School Review, online. “White Students are Now the Minority in U.S. Public Schools.” 14 October 2019. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/white-students-are-now-the-minority-in-u-s-public-schools Reading Rockets. “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors.” [YouTube video] 30 January 2015. https://youtu.be/_AAu58SNSyc Reynolds, Jason and Ibram X. Kendi. Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You: A Remix of the National Book Award-winning Stamped from the Beginning. Little Brown Books for Young Readers, 2020. School Library Journal, “An Updated Look at Diversity in Children’s Books.” June 19, 2019. https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=an-updated-look-at-diversity-in-childrens-books Singleton, Glenn E. Courageous Conversations About Race: A Field Guide For Achieving Equity in Schools. Corwin: 2015. Style, Emily. “Curriculum as Window and Mirror.” From National Seed Project, published in Social Science Record, Fall 1996. http://www.nationalseedproject.org/images/documents/Curriculum_As_Window_and_Mirror.pdf Teaching Tolerance. Let’s Talk: Facilitating Critical Conversations with Students (online resource, revised Dec 2019) https://www.tolerance.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/TT-Lets-Talk-December-2019.pdf Tippett, Krista with Jason Reynolds. “Fortifying Imagination.” On Being [Audio Podcast]. 25 June 2020. https://onbeing.org/programs/jason-reynolds-fortifying-imagination/?fbclid=IwAR0ioB9ZwIBvOXRf9gaYDI4prtyXnOM-gX755oe8WEI51bOhpjiAm99mT28 Woodson, Jacqueline. Personal Video Recording. Author Appearance at Barnes and Noble in Union Square, New York City, October 2018. BLOG POST BY PTAC MEMBER Dr. JESSICA D. REDCAY I have a lilac bush in my yard that no longer blooms after I transplanted it. I researched why it would not bloom, and I learned that sometimes lilac bushes stop blooming after being traumatically transplanted. It was necessary that I transplanted my lilac bush, but I still miss seeing it bloom. I feel like my second graders were like my lilac bush during the pandemic. They had to quickly be uprooted for their own safety. I had to be creative with the approaches that I used virtually to help my little lilacs bloom during remote learning. I didn’t want to just provide students with worksheets to complete. Rather, I wanted to find ways to spark their curiosity and interest as they continued to learn remotely. Also, I didn’t want my students to feel like they were completing a To-Do list to earn a participation grade. Rather, I wanted my students to create things, learn, connect, and have fun. This blogpost will highlight some of the key elements of my remote learning journey that might help you as you work to adapt teaching during the pandemic. Virtual Reality (VR) Tours Since the students had to stay home and never got the VR goggles, we had to use VR in a different way to explore the world. My students went on virtual field trips to places like: Grand Canyon, Hawaii, San Diego Zoo. The students used Google Earth to explore different places in the world, and they could move around within the different places. Within the zoo, students were able to watch live animal webcams. Students used these experiences to act as writing prompts. These shared experiences helped the students connect with one another, and increase student engagement levels. We used Google Virtual Reality Tours, San Diego Zoo Live Cams, American Museum of Natural History, etc. However, our favorite tour was the one I created using a 360 degree camera and Google VR Creator of our physical classroom. The students wrote about things that they learned from the Virtual Reality Field Trips. Information was embedded within the virtual tours. Students had the option to write with paper or pencil or the students could use Primary Writer. We displayed their writing in a media file within Schoology. Digital Breakout Experiences My student teacher (Tina McDaniel) created a digital breakout experience to match the content we were teaching. This helped increase student engagement levels because the students were learning content for a specific purpose and wanted to complete the breakout activity. Miss McDaniel designed a Google Site for the escape room experience to provide students with ease of use and one resource for young children to follow. Thinglink is another great tool that you can use if you do not want your students to get confused by clicking into multiple sites. I created a States of Mater Thinglink as a reference for my students with embedded information. Within the digital breakout, my student teacher created fake text messages and newspaper clippings. The students had to solve different e-puzzles too. Here are the different tools that were used to create a digital breakout. Also, Breakout EDU has different free digital breakouts to use in the classroom, too. Digital Scavenger Hunts Digital Scavenger Hunts are wonderful because it gets students moving. There are different platforms that can be used to create this type of activity. You can use other platforms like: Padlet, FlipGrid, GooseChase, GoogleSlides. We used FlipGrid to create our own FlipHunt. We gave students a prompt to find different things. Then they had to respond with a video showing what they found. The prompts I included were short video prompts. For example, my students had to measure the average length of different animals with sidewalk chalk. My students had to take pictures of different 3D shapes that they found within their home. Here are some more examples of the digital scavenger hunts that we used during remote learning. Give it a Try Remote learning has been challenging for everyone, but we are all in this together. One of PTAC 2020-2021 Recommendations stated “We recommend teachers receive training on relevant new technologies. If remote learning must occur, teachers should have access to professional development on effective remote teaching practices and technologies for their content areas.” Virtual Reality, digital breakout experiences, and digital scavenger hunts are excellent ways to leverage technology in the classroom. However, teachers need training. Schools need to provide training and proper support. When possible, school district leaders should ask teachers about what they would like to learn more about, and they can provide teachers with options. Differentiated professional development helps teachers hone their craft of teaching while accounting for different experiences of teachers. When teachers are willing to try new things, they can help foster creativity and learning for our students. It is tough, but we know that we can do it together because we want to find the best way to help EVERY learner bloom! |

AuthorPennsylvania Teachers Advisory Committee Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed