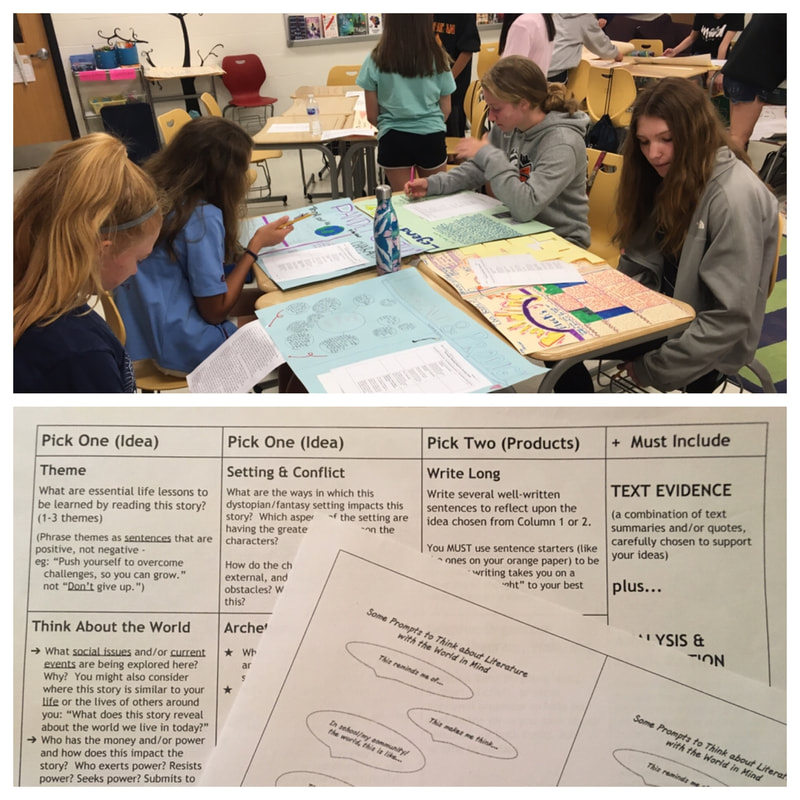

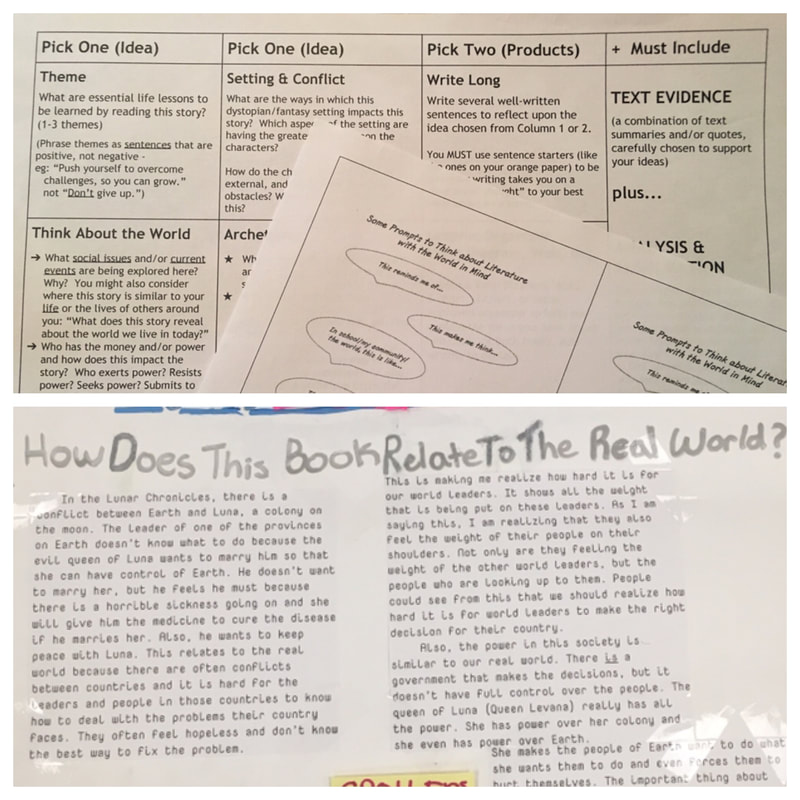

Blog post by PTAC Member Tracey Fritch Four years ago, after spending more than twenty years teaching elementary-aged students, I accepted a job working with middle schoolers. While teaching is, of course, teaching - no matter what age - making the switch to middle school from elementary school required adding plenty of new tools to my toolbox. One of the most important lessons I’ve learned during these past four years are ones about the power of choice to reach this particular group of kids. A common choice middle schoolers and their teachers face is the making of behavioral decisions. Some of the best advice on working with middle schoolers was wisely imparted by one of our guidance counselors: when faced with a standoff, “give them a choice.” Offering behavioral choices saved me from more showdowns than I can count - giving a child a chance to save face in front of peers and the classroom a chance to return to work with minimal disruption. Since my teaching team serves about 100 students each year, academic choices were, at times, more complex to implement. In my district, we use reading and writing workshop with all of our students K-8, and our students are given lots of choices about the content of their independent reading and/or writing each day. Our teachers confer with students about their work and set them on paths for self-improvement, but doing this work one-on-one was time-consuming. With so much to cover in the course of a school year and only 44 minutes per day in which to do it, offering more choices related to teaching, learning, and assessment seemed improbable to a newer middle level educator. Small-group strategy lessons have been an answer. Based upon the advice of our curriculum writers, the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project (TCRWP), and Teaching Learning Succeeding (TLS), this year I began offering my students more formative assessments (TLS calls them “targeted checks”), based upon what we thought were the most essential learning objectives of any given unit. Armed with these targeted checks, I compiled materials for running high-utility strategy groups. A few students in these groups were invited to particular groups because their formative assessments told me that they needed to be there; others joined because they self-identified as wanting to improve upon a specified skill. In these small groups (4-6 people), students who’d previously scoffed at the idea of doing challenging writing revision work when I’d suggested it to the whole class gave me their rapt attention as I offered advice on how they might go about being more successful with a skill - accompanied by a “take along with you” menu of choices for how to go about this work. Nearly all students immediately set about the job of making needed changes to their pieces, impatient to offer the revised pieces for feedback when finished. I attribute much of this buy-in to the fact that they had a choice - sometimes even in whether or not to work on a skill but always in how (which strategies on the menu) and where (in their pieces) to go about incorporating a skill into their repertoire. One final way I offered greater choices to my students this year was in terms of end-of-unit assessment. When our TLS staff developers encouraged us to offer students “Challenge by Choice,” I also remembered a TCRWP workshop I’d recently attended on using “Learning Menus.” These menus offer students a chance to choose how and where they might analyze and respond to complex texts. Previously, we’d asked students to show what they’d learned in a number of our units by writing Text Dependent Analysis essays. We needed them to practice writing in this format, and they needed a way to show us what they’d learned in a particular unit. It seemed, in some ways, like the path of least resistance and a way to marry our curriculum with state requirements. Though it seemed like the path of least resistance since our curriculum asks students to read, talk and analyze complex texts in deep, thoughtful ways, gauging what they knew at the end of a unit by using a format that doesn’t exactly spark creativity wasn’t working out as we’d hoped. This year, wanting to offer students appropriate differentiated challenges, I decided to try the “Learning Menus” when we finished our Dystopian Book Clubs unit of study. This unit asked our seventh grade readers and writers not only to read, understand and analyze these complex texts but also asked them to realize that dystopian authors are often writing thinly-veiled social commentary - and to make connections to the social issues existing in our world today. This was a tall order for young teens but a developmentally appropriate one for these students who are so full of passion to unpack and discuss what’s fair and unfair in their worlds as they begin to make their way toward adulthood. The “Learning Menus” are based on the “Value Menus” in fast-food restaurants, encouraging students to choose from among a variety of essential understandings from the unit upon which to focus as well as a variety of ways to show what they learned - from essay-writing to organizing to illustrating, in order to demonstrate their understanding of the work of a unit of study. Students created their “value meals,” their final projects, in unique ways, choosing (within teacher-created parameters) what aspects of the unit on which to focus and how to present their ideas about what they learned. For this particular project, one choice was about how to reflect upon how their texts connected to the world considering theme, social issues, or their author’s intent to change the world with the text. A second choice involved how they understood text elements: setting/conflict, archetypes, or character traits. Many students crafted responses that were much more thoughtful and outside-the box than any formal essay assignment could have drawn from them. Some shone with their descriptive ability, some with their ability to organize ideas into tidy graphic organizers, and many more than I’d anticipated labored over gorgeous sketches. The middle school years are an exciting, dynamic time of life marked by dramatic physical and emotional changes as students begin to navigate young adulthood. At the same time, many students find themselves unconvinced as to the ways that their school coursework is relevant to their real lives and also find themselves completing assignments merely to please their teachers and families and get by with just enough effort to earn whatever is considered an acceptable grade in their households. The power of choice as a classroom tool can win over adolescent’s minds and hearts and make these years a time when they are invested in their work as opposed to being merely compliant. With a bit of planning, differentiated choices, based on student ability and interest, can help teachers in all subject areas foster creativity, purpose and engagement in their classrooms, even with those students who are the most skeptical about why they are with us in the first place.

2 Comments

|

AuthorPennsylvania Teachers Advisory Committee Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed