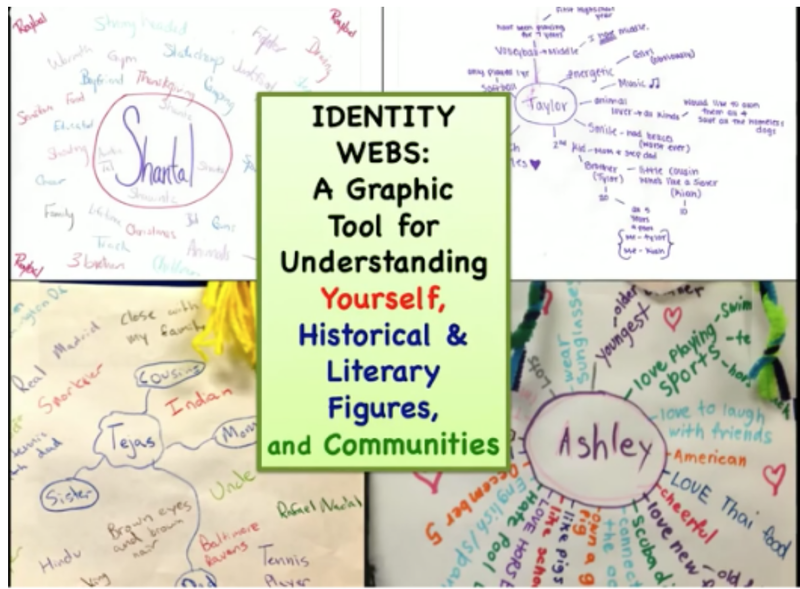

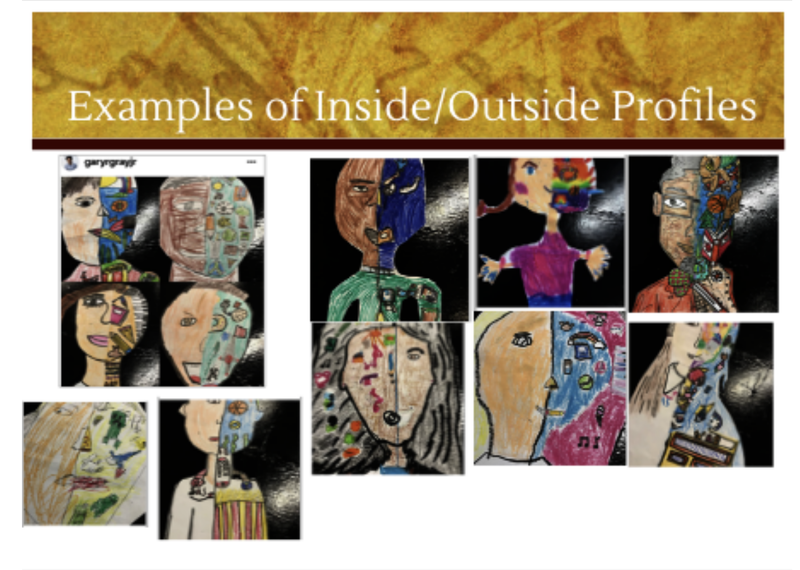

BLOG POST BY 2014 PA TEACHER OF THE YEAR FINALIST AND PTAC MEMBER TRACEY FRITCH AND Julie MIKOLAJEWSKI In her 2018 New York Times bestselling book, So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo states,“You have to get over the fear of facing the worst in yourself. You should instead fear unexamined racism. Fear the thought that, right now, you could be contributing to the oppression of others and you don’t know it. But do not fear those who bring that oppression to light. Do not fear the opportunity to do better.” So You Want to Talk About Race grew from Oluo’s experiences in attempting to personally unpack and explain challenging issues related to race and racism, then realizing she had a knack for helping people figure out how to engage in conversations about race, with the hope of making progress and creating change. Now, more than ever, in spite of the challenges inherent in facing and discussing important social issues, including the challenges encountered during conversations about race, public school teachers must cultivate culturally responsive teaching in their classrooms. They must strive to model the process of creating connections with others, especially those who are different from themselves, all the while working to participate in and foster authentic classroom conversations about social issues, thus encouraging and teaching students to do the same. This past June, the Pennsylvania Teachers Advisory Committee (PTAC) issued its “Recommendations for the 2020-2021 School Year.” Inside the first recommendation on student well-being was this statement: “We recommend every school district embrace culturally responsive teaching and learning. This should incorporate history inclusive of marginalized perspectives and literature that represents and celebrates diverse cultures and individuals.” Though many people, including many well-meaning educators, avoid what they perceive to be challenging conversations about race or other social issues for many reasons, including fears of making mistakes or being perceived negatively, it has become increasingly clear that, for many, the choice to avoid these conversations is a privilege. Given recent world events, this is a privilege onto which we can no longer afford to hold. As Maya Angelou famously stated, “When you know better, you do better.” Each day, our students look to us for guidance and leadership regarding both their academic and their social-emotional learning; as we foster culturally responsive classrooms, we provide safe spaces in which a diverse range of individuals feel included, supported, and able to thrive. Identity Work In order to be culturally responsive and to fully prepare our students for the mutli-dimensional world in which they live, teachers must choose to address recent events of racism, discrimination and bias in the news, as well as acknowledge that events like these are not new occurrences. Students are keenly aware of the current socio-political climate and are looking to the adults in their lives to offer guidance in both processing it and in discussing it openly and respectfully with others. Taking time to foster conversations about identity, diversity, and character development are not only best practices in literacy learning, but these conversations also foster classroom community development and prepare students to be educated and engaged citizens in a democratic society - hopefully a society that is inclusive and promotes understanding of equity and the strength of diversity. This diversity includes diversity of race, ability, gender preferences, and sexual orientation, among others. At a middle school in a Philadelphia suburb, Tracey begins each year with her students by asking them to create “identity webs,” a ritual learned from the professional book Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry, by Smokey Daniels and Sara Ahmed. Students spend time, in class and at home, examining, listing, and discussing the various aspects of their “identities.” This list includes, but is not limited to, student reflections upon age, grade, gender, hobbies, passions, culture/ethnicity, languages spoken, favorite foods, personality traits, and family composition. Students share whatever information feels comfortable as they use the webs to introduce themselves to classmates, and learn about the ways they are both similar to and different from others, as they build classroom communities. Similarly so, Julie begins the year with students creating identity portraits that depict both visible and invisible aspects of her students’ identities. This activity was borrowed from Gary Gray Jr., an educator in Singapore. Initially, these conversations about personal identities can be tentative and even awkward, but they gradually evolve, with encouragement and guidance, into frank, empathic conversations, and set the tone of these classrooms as - this is a place where we respectfully discuss important matters, even when it sometimes feels initially uncomfortable to do so. Inevitably, discussions about students’ personal identities lead to literary discussions of the identities of the characters in the novels they read, and the ways those identities shape the characters’ perspectives and choices. Later, as these middle schoolers compose poetry, they often choose to reflect upon various aspects of their identities from a social justice standpoint; they consider the way their identities shape their lives, impact their choices, and guide the ways in which they hope they can impact the world. As well, when students create characters for their fiction stories, they first envision the characters’ identities, and the way those identities will shape their characters’ responses to, and solutions for, the conflicts in the stories. What begins as highly personal work leads to cultural awareness, authentic opportunities for personal growth and self-expression, as well as participation in respectful discourse about identity and social issues. Diversifying Classroom Libraries & Fostering Diversity in Student Independent Reading Alongside the crucial nature of open, respectful classroom conversation, students also need to be offered authentic ways to explore a wide variety of cultures and perspectives, including ones not directly represented in a classroom community. Though students of color currently comprise more than 50% of U.S. public school students (Public School Review, October 2019), according to the School Library Journal (in 2018) only around 23% of children’s books published had a main character that was a child of color. This startling disparity underscores not only the need for culturally relevant pedagogy, but also a need for increased diversity in the composition of classroom and school libraries. In 1990, Rudine Sims Bishop coined the now-famous metaphors of books serving as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. In a video interview published by Reading Rockets in 2015, when asked why children and schools needed diverse books, Bishop answered: "We need diverse books because we need books in which children can find themselves, see reflections of themselves… children need to see themselves reflected. But books can also be windows. And so you can look through and see other worlds and see how they match up or don’t match up to your own. But the sliding glass door allows you to enter that world as well. And so that’s the reason that the diversity needs to go both ways. It's not just children who have been underrepresented and marginalized who need these books. It’s also the children who always find their mirrors in the books and, therefore, get an exaggerated sense of their own self-worth and a false sense of what the world is like, because it's becoming more and more colorful and diverse as time goes on." As we live through these times of dramatic social change, it is imperative that teachers and schools provide students with texts that incorporate the full complexity and variety of human beings who exist in the world - and include protagonists that represent the full diversity of the human experience. The idea that books can, and should, be windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors for students is not a new one, but, now more than ever, this concept needs to move to the forefront in order for educators to ensure that not only are the students seeing themselves in the books that they read, but that students are also grappling with the complex nature of human identity, particularly related to individuals who have different lived experiences from their own. By cultivating the practice of reading texts that offer opportunities for students to perceive others in the world more authentically, students gain empathy, cultural competence, and can then more adeptly engage in the work of equity, empathy, and anti-racism. Diversifying classroom and school libraries is an ideal first step for educators seeking to develop cultural competence in their students. At times, as teachers begin to think about taking on challenging conversations, many wonder if certain topics are “too much.” While it is, of course, essential to consider developmental appropriateness of texts for various ages, most children and young adults have natural curiosity and deep empathy for others’ lives, and are eager to learn about and discuss others’ experiences. Newbery Medal winner and past National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature Jacqueline Woodson is often asked about the ways in which she takes on what some might consider challenging topics in her books. To answer, she notes that her work as an author, particularly one for tweens and teens, has taught her that children are acutely aware of issues in the world and that they truly want the important stories of their and others’ struggles to be seen, heard, and understood. In addition to the way that reading books about diverse characters promotes empathy and understanding, these books also provide natural and authentic ways to open necessary discussions. In an author appearance in fall 2018, Woodson noted, “There is so much history in this country around the way people were and continue to be mistreated - and the challenge is, always - how do I tell this story in a way that’s not didactic? How do I tell this story in a way that’s respectful and loving? And how do I tell this story in a way where I can show the hope in it? And that’s always timely, that need for hope in a narrative.” Reading and discussing well-written, engaging children’s books affords teachers a natural and authentic opportunity to talk with kids about race, bias, and discrimination of all kinds, as these topics arise. Because of the presence of a beloved character and engaging narrative, the conversations are not, as Woodson says, “didactic,” but instead, thoughtful, thought-provoking and empathic. If a teacher or school librarian is at the beginning of this journey in diversifying a library, they should begin with what they have, inventorying their libraries to look at the types of books which are (and are not) there. Educators should first eliminate outdated books with stereotypes, identify the themes and identity groups that are somewhat lacking or not present, and then begin to purchase well-written titles based on recommendations from others further along in the journey; following thought leaders in the field on social media is an excellent way to find new favorite authors. Students and families often enjoy helping with this work, noticing trends in a library and making suggestions for improvement. Thrift stores, online yard sales, and library sales are excellent, inexpensive resources in quickly adding numbers of books, as are used booksellers such as Better World Books, which donates a part of its profits to causes that bring books to people in need. Donors Choose and First Book are also helpful in raising funds for building libraries. Scholastic book orders and book fairs yield “points” with which teachers may purchase books. When asked, friends and family members who have finished with books in their homes will often happily donate them to a school. In addition, in many districts, some curriculum funding in schools can be successfully redirected toward adding authentic literature choices, and away from more traditional textbook/workbook options, often for far less money and with the result of far greater student engagement. For more information on diversifying classroom and school libraries, including choosing diverse authors for addition to (particularly middle school) libraries, click here. Please feel free to share in the comments if you want to suggest someone we’ve missed! Once the new books begin to arrive, it is important to get them into students’ hands. Simple routines that create a “buzz” around particular novels or authors often have immediate and significant impact - teachers and students can create “book buzzes” (or author buzzes), in which they describe aloud or in writing what aspects of particular books/authors they enjoyed, and to whom they might recommend them. This also works by placing books on a white board ledge with a quick note jotted above it. Typically an early-in-the-year routine, Book Tasting (like wine tasting) allows students to quickly peruse and “sample” a teacher’s library, noting titles of interest and discussing them with others. These routines result in what is known as “blessing” of those books and authors - and circulation of them increases dramatically. In these times of social distancing and virtual learning, these procedures would likely need to be adapted, but can still take place. It is important to include both widely-relatable books about everyday experiences such as friendship that happen to feature a diverse variety of characters, as well as to include books focused on “social issues” related to those characters - lest we give students the impression that children of color, children with disabilities, and/or children with differences in gender identity or sexual orientation (or other ways of being diverse) only have lives fraught with upheaval related to those identities. Over time, we need to find ways to continually track the balance of texts in libraries - many students enjoy sorting and categorizing books and helping with this work (though perhaps this will be a more appropriate activity once our current pandemic ends); it can also be helpful to use the free web tool, Booksource Classroom Organizer, which, once set up, will not only perform library audits to check for diversity, but also offers a free online platform with which to manage no-contact book checkout. Delving into Deeper, More Courageous Conversations After the initial “buzz” over these books and authors is created, teachers can begin to delve into the deeper conversations naturally inspired by the literature and identity work. While facilitating these conversations can be a complex task requiring effort and care, it remains an extremely important one. Despite the fear, discomfort, or reservations that teachers may have, we are long past the time in which it is appropriate for these conversations to be avoided; thankfully, there are many excellent resources to support us in doing so. Teaching Tolerance offers a guide titled Let’s Talk (2019) that can be an excellent springboard for teachers just starting out. Two other helpful resources in framing and structuring this discourse come from the work of Glenn Singleton (Courageous Conversations About Race) and Diane Goodman. Among other ideas, Singleton’s “four agreements” help to foster spaces that eventually allow for deep dialogue about race, racism, ethnicity and privilege. Participants are encouraged to “stay engaged, experience discomfort, speak your truth, [and] expect and accept non-closure” (70). On her website, Diane Goodman offers resources on building cultural competence for promoting equity and inclusion, and also shares sentence frames for crafting responses to the microaggressions and bias which will arise up in fledgling, honest conversations about culture and race. Unavoidably, conflict, discomfort, and non-closure will occur in these conversations, however, teachers must encourage children to continue to engage in the conversations, despite these difficulties. Singleton reminds his readers that ‘mistakes” and misconceptions will happen, but by staying engaged, students’ communities can become places of healing and change. In his best-selling 2019 book, How to Be An Antiracist, Ibram Kendi advises his readers to eliminate the term “racist” as a slur or pejorative about a particular person. Instead, he asks us to use the word descriptively, as “the only way to undo racism is to consistently identify and describe it” (9). Once we can observe, describe, and discuss racist actions, thoughts, statements, systems or policies (or classist, sexist, ableist, or homophobic ones), we can then begin to go about the work of unpacking and dismantling them. Both authors of this blog post, though they teach in different school environments, one large urban and one suburban, utilize reading and writing workshops as their adopted literacy curricula. This allows us a fair amount of curricular freedom in adding diverse texts to the curriculum and encouraging our students’ independent reading of a wide variety of diverse texts. However, even teachers whose curriculum is more scripted or laid out on their behalf usually still have some agency in choosing short mentor texts for demonstrating teaching points, in choosing more diverse whole-class texts for longer-term study, and/or in encouraging and guiding students’ independent reading lives. The more that, through diverse texts, students are exposed to a greater variety of lived experiences and challenges, the more they encounter identities different from their own, the easier it will be to broaden horizons in a way that fosters greater cultural competence, and, hopefully, eventually, inspire positive actions for creating a fairer world for all. Moving Forward Recently, Newbery author and current National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Jason Reynolds was featured as a guest on the “On Being” podcast with Krista Tippett. A Newbery winner, and passionately devoted to children’s well-being, Reynolds has most recently published what he calls the YA “remix” of Ibram Kendi’s powerful and ambitious historical text, Stamped from the Beginning. During the podcast, Reynolds noted that creating “fortitude in the minds and bodies and spirits of young people” is his calling. The topic of Reynolds and Tippet’s podcast conversation was “Fortifying Imagination.” He says this about culturally relevant pedagogy and talking with students about antiracism: "They know. And so, if they know and we’re not helping them process, now it’s become more dangerous than you’ve ever imagined. So, we have an opportunity to lean into the discomfort of having to talk to kids about this, in order for them to find language around it... But how does one keep an imagination fresh in a world that works double-time to suck it away?... I think that the answer is, one must live a curious life. One must have stacks and stacks and stacks of books on the inside of their bodies. And those books don’t have to be the things that you’ve read—that’s good, too, but those books could be the conversations that you’ve had with your friends that are unlike the conversations you were having last week. It could be about this time, taking the long way home and seeing what’s around you that you’ve never seen… What if you were to explore the places around you? What if you were to speak to your neighbor and to figure out how to strike a conversation with a person you’ve never met? What if you were to try to walk into a situation, free of preconceived notions, just once? Once a day, just walk in and say, I don’t know what’s gonna happen, and let’s see. Let me give that person the benefit of the doubt, to be a human… There’s no finish line...It’s a muscle that has to be developed...antiracism is simply the muscle that says that humans are human. That’s it. It’s the one that says, I love you, because you are you. Period. That’s all." This beautiful conversation was reminiscent of the way that Woodson, in her bookstore appearance, acknowledged the need for “hope in a narrative,” and of the way Oluo asks us not to “fear the opportunity to do better.” In these turbulent times, educators would do well to begin the process of cultivating culturally responsive teaching in their classrooms through literature - leading to conversations that are both authentic and sometimes uncomfortable - but the sort of productive discomfort that leads to growth and systemic change. Our children are watching us - and waiting for us to provide guidance - they need to hear our (and each others’) voices as we do the hard work of guiding them toward the hope in our nation’s narrative. Not surprisingly, the best way for educators to find “hope in the narrative” is when we see the way that culturally responsive instruction inspires students to consider and share their own identities in the work they create - both in writing and in classroom projects and conversations. Two talented and introspective seventh graders, Gurnoor, a young woman of color, and Justin, a young man working to learn to manage his anger more effectively, wrote the following poems after studying mentor poems and poets in a middle school writing workshop, while learning virtually in the spring of 2020. Sources Cited

Daniels, Harvey “Smokey,” and Sara K. Ahmed. Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry. Heinemann, 2014 Goodman, Diane. www.dianegoodman.com. “Responding to Microaggressions and Bias.” https://dianegoodman.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Responding-to-Microaggressions-and-Bias-Goodman.pdf Goodman, Diane J. www.dianegoodman.com. “Cultural Competence for Equity and Inclusion: A Framework for Individual and Organizational Change.” 20 April 2020. https://www.wpcjournal.com/article/view/20246 [Summary at: https://dianegoodman.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CulturalCompetenceforEquityandInclusionDianeGoodman.pdf] Institute for Educational Leadership. “Courageous Conversations About Race Protocol Overview.” https://iel.org/sites/default/files/G10-courageous-conversation-protocol-overview.pdf Kendi, Ibram. How to Be an Antiracist. One World, an imprint of Random House, 2019. Oluo, Ijeoma. So You Want to Talk About Race. Seal Press: 2018 Public School Review, online. “White Students are Now the Minority in U.S. Public Schools.” 14 October 2019. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/white-students-are-now-the-minority-in-u-s-public-schools Reading Rockets. “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors.” [YouTube video] 30 January 2015. https://youtu.be/_AAu58SNSyc Reynolds, Jason and Ibram X. Kendi. Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You: A Remix of the National Book Award-winning Stamped from the Beginning. Little Brown Books for Young Readers, 2020. School Library Journal, “An Updated Look at Diversity in Children’s Books.” June 19, 2019. https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=an-updated-look-at-diversity-in-childrens-books Singleton, Glenn E. Courageous Conversations About Race: A Field Guide For Achieving Equity in Schools. Corwin: 2015. Style, Emily. “Curriculum as Window and Mirror.” From National Seed Project, published in Social Science Record, Fall 1996. http://www.nationalseedproject.org/images/documents/Curriculum_As_Window_and_Mirror.pdf Teaching Tolerance. Let’s Talk: Facilitating Critical Conversations with Students (online resource, revised Dec 2019) https://www.tolerance.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/TT-Lets-Talk-December-2019.pdf Tippett, Krista with Jason Reynolds. “Fortifying Imagination.” On Being [Audio Podcast]. 25 June 2020. https://onbeing.org/programs/jason-reynolds-fortifying-imagination/?fbclid=IwAR0ioB9ZwIBvOXRf9gaYDI4prtyXnOM-gX755oe8WEI51bOhpjiAm99mT28 Woodson, Jacqueline. Personal Video Recording. Author Appearance at Barnes and Noble in Union Square, New York City, October 2018.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPennsylvania Teachers Advisory Committee Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed